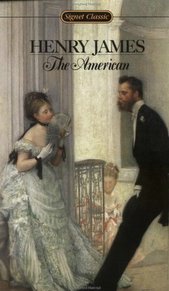

The American by Henry James

This was a reread, I think the third time, but I haven’t read it since the mid-Seventies at the latest. Rereading, I must say, was a huge enjoyment. This is James at the best of his earlier period, where he was exploring the naïve American in Europe, packing enormous meaning in every sentence, but before he began with the super subtle detail and very long and complex sentences that characterize his later masterpieces like A Portrait of a Lady, The Ambassadors, The Wings of the Dove and The Golden Bowl. [By the way, the difference between James’ long sentence and Faulkner’s is simple: James are architected sentences that depend on intricacies of English syntax while Faulkner’s sentences are not so complex as they are conversational and accretive, where he adds and modifies rather than subordinates.]

This was a reread, I think the third time, but I haven’t read it since the mid-Seventies at the latest. Rereading, I must say, was a huge enjoyment. This is James at the best of his earlier period, where he was exploring the naïve American in Europe, packing enormous meaning in every sentence, but before he began with the super subtle detail and very long and complex sentences that characterize his later masterpieces like A Portrait of a Lady, The Ambassadors, The Wings of the Dove and The Golden Bowl. [By the way, the difference between James’ long sentence and Faulkner’s is simple: James are architected sentences that depend on intricacies of English syntax while Faulkner’s sentences are not so complex as they are conversational and accretive, where he adds and modifies rather than subordinates.]The story is of Christopher Newman (new man, right? Not only from “the new world” but from “the West”, practically a hero riding on a white horse) who left school very early somewhere in the East and by 35 had made himself a millionaire businessman in California. He wakes up one morning and thinks there must be more to life. Like other Americans of his generation who can afford it he heads for Europe to learn about the rest of life. In Paris—for James always the center of European culture—one of the first things he does is order several paintings from a beautiful young girl copying paintings in the Louvre—always supervised by her father. We gradually come to realize that Mlle. Noiche is a very bad painter. Later she plays a more sinister role in the plot but early on Newman’s business relationship with her and her father (who teaches him some conversational French) helps to establish Newman’s naiveté.

Newman thinks he will look for a wife in Paris and an ambitious American ex-patriot rather mischievously suggests Madame de Cintré, widowed daughter of the late Marquis de Bellegarde. Her family is 1000 years old. Her older brother, the present Marquis, declares his loyalty to the Bourbons and refuses to go to the Napoleonic Court. Claire de Cintré, it is clear, was married young to an old man chosen by her family who has mercifully died before the story begins. She is beautiful, delicate, shy and completely under the thumb of her family. Nevertheless she is drawn to Newman and for whatever reasons after some initial insults her mother and brother agree to the marriage. While you must have the patience to wait for James to set the scene, the novel contains a full measure of suspense so I’ll not give away the plot, except to suggest that aristocratic French families have traditionally looked down their noses at "commercial men".

Finally, I was struck by how completely and effectively James followed his own theory of narrative point of view in The American. All readers recognize that novels are most often told from the point of view of a third person narrator (often not even identifiable as a person) who “knows everything” or from the point of view of one person, in which case the author has to work hard to give the reader knowledge that the narrator doesn’t have. James thought there was a better way. He called it “centre of consciousness” and it’s so familiar now we rarely single it out, but James used it to radically change narrative from the 19th century “dear reader” style to something much more subtle. James described it as the narrator looking through the back of the character's head, seeing what he sees, though described from the larger experience of the invisible narrator. It combines the virtues of the omnipotent narrator and the first person narrator. Here James uses detail brilliantly to characterize both Newman and the people he interacts with, always telling the reader far more than Newman understands, but rarely revealing who’s telling the story.

I just heard a piece on NPR this morning about Scotland and its smoking ban in all enclosed places—soon to be extended to all of Britain. What I didn't know was that the ban will extend to film sets so that Winston Churchill cannot be portrayed with his cigar. Although California has similar laws, movie sets obtain "industrial permits" of some sort to allow smoking on sets. Since I just saw George Clooney's

I just heard a piece on NPR this morning about Scotland and its smoking ban in all enclosed places—soon to be extended to all of Britain. What I didn't know was that the ban will extend to film sets so that Winston Churchill cannot be portrayed with his cigar. Although California has similar laws, movie sets obtain "industrial permits" of some sort to allow smoking on sets. Since I just saw George Clooney's