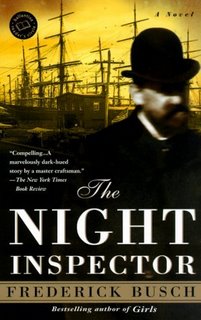

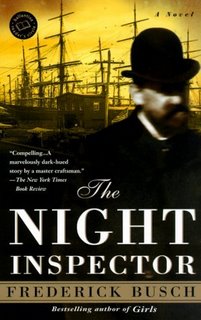

It's a coincidence that the next book I read after the Civil War history was about a man who was a sharpshooter in the Civil War whose successful career ended when an enemy bullet hit his rifle, causing it to explode in his face. Billy Bartholomew wants to die, is nursed back to health, and decides the best way to deal with his awful disfigurement is to have the maker of prosthetic limbs make him a mask to cover his face. That sets the scene for this dark and twisted novel of post-Civil War New York.

It’s a novel that juggles lots of idea that fascinate most of us: the mask immediately suggests the duality of reality and illusion as war asks us always to consider whether killing is always murder or not. Interestingly, Billy Bartholomew, the main character and narrator of this novel, says he posed for Winslow Homer’s famous painting, "The Sharpshooter on Picket Duty". Of interest too is that fact that Homer had this to say about his painting (which Billy does not report): "The impression struck me as being as near murder as anything I could think of in connection with the army & I always had a horror of that branch of the service."

When considering the morality of killing in war, Busch removes the “good of the cause” from consideration because Billy says that Abe Lincoln, preserving the union and freeing the slaves are a blind and that the war was really about the need of Northern industrialists for blacks to be low-paid workers in their factoriesa—“totally hindsight view” one can’t help but wonder? In other words it’s all economic. But then it’s not as if Billy holds himself aloof from the profit motive, becoming a successful (and ruthless) commodities trader in New York after the war. So the ideas all revolve around moral ambiguities as I see it.

Moral ambiguities suggests the inclusion of another character in the novel: M is clearly Herman Melville, living—barely supporting his family as a night inspector for the US Customs Service—on East 26th Street. Bartholomew knows of and admires

Moby Dick, but is not aware of other novels like

Pierre or The Ambiguities and

The Confidence Man. Melville’s literary success is years behind him and he’s aware that most admirers assume that he is dead.

Billy lives in the Five Points area of New York, a notorious slum of the time that provided life and sustenance for Irish, German and other immigrants. There was a major archeological investigation at the site of a US courthouse bginning in 1991. Archeologists were able to reconstruct much about the life of the people who had inhabited the Five Points area, both in Bartholomew’s time and before. One can’t help but wonder if that might have stirred up Busch’s imagination, to say nothing of his interest in the time and the place. In any case, one of the compelling aspects of the book is the recreation of life on the NY streets—especially at night when one might even by threatened by a wild boar—in the post-Civil War period.

The novel’s plot involves Billy’s attempt to help his lover, a beautiful Creole prostitute named Jessie, free some black children who are being shipped to New York in barrels to be sold under cover as slaves. Naturally he needs the help of his friend the night inspector (Melville). As the novel draws to a close, this violent plot takes over and the novel comes to a crushing conclusion which leaves the whole moral ambiguity question even murkier. There are still two chapters to go, though, when the slaves-in-a-barrel plot is concluded. In one, Billy sees not only M but Mark Twain in the audience for one of Dickens’ readings and identifies Twain by the name he gave to the age that’s just beginning, “The Gilded Age”. In the other, Billy is seen as a couple with the Chinese laundress who is the only other person besides Jessie who ever saw him without his mask, presumably suggesting a return to the human fold for this violent and disturbing man.

Like most novels of ideas, this one is overbalanced by the ideas, but it does some things very well: it explores the violence that humans do to each other in a context that reserves judgment on right and wrong and instead considers human and inhuman values and reactions, and it explores 19th New York—the urban model of life which was the “winner” in the Civil War—with all of its contradictions and ambiguities, giving readers a sense of the range of people who lived there, what they did and how they lived.

A short novel that’s billed sometimes as a “mystery”. That's a stretch, though there is a mystery of sorts and even a family of swindlers. It’s really a philosophical novel, with a generous dose of humor. Novels that honor ideas more than human interactions and situations are not my favorites—I’d rather read existentialist thinkers than the novels they write. That must be my peculiarity, though, since I find most people quite puzzled by my preferences.

A short novel that’s billed sometimes as a “mystery”. That's a stretch, though there is a mystery of sorts and even a family of swindlers. It’s really a philosophical novel, with a generous dose of humor. Novels that honor ideas more than human interactions and situations are not my favorites—I’d rather read existentialist thinkers than the novels they write. That must be my peculiarity, though, since I find most people quite puzzled by my preferences.